“Caring for our past” is a journey through the Ukrainian caregivers community in Italy, which began at the end of 2021 and lasted until June 2023. This project started from my personal story since my grandmother was assisted by an Ukrainian caregiver who later introduced me to the community. It was born as an investigation on the role of caregivers in Italians’ houses and from when the war broke out it continued documenting the feeling of leaving a conflict from afar.

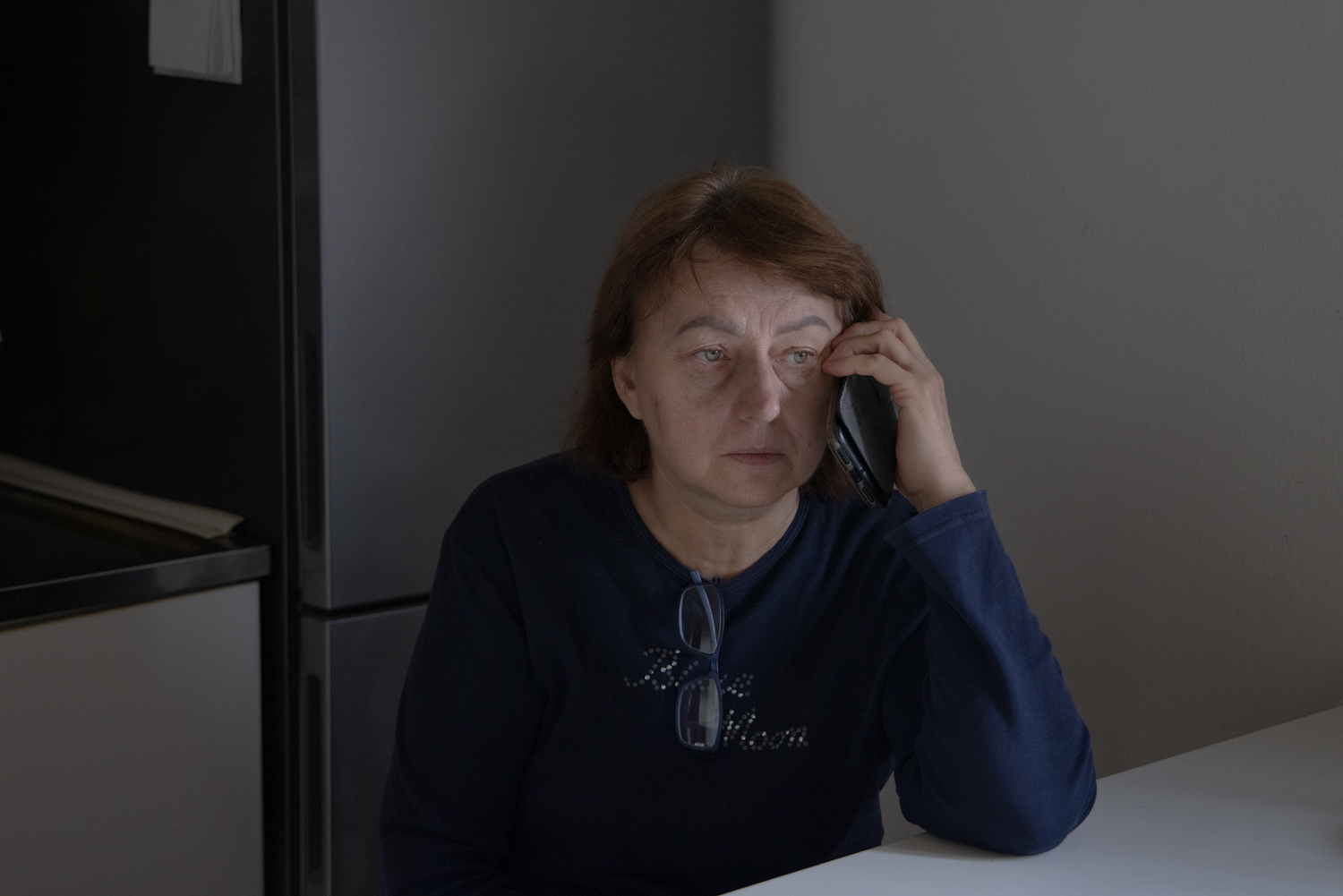

Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, among European Union member states, Italy was home to one of the largest communities of people of Ukrainian origin. According to data from the EU, over 200,000 citizens were living in Italy as of late 2020. This migration made them one of the most rooted groups in the country, largely composed of women employed in family and health services for the elderly. My grandma was one of them. In 2020, after getting COVID, she was no longer autonomous. For this reason, my family decided to hire Lyubov Mala, an Ukrainian caregiver. This project begins in my childhood home, where I was curious about Lyubov’s choices to live and work in Italy. The profession of caregiver is among the last places in the job market, even though most people have a good level of education and many were qualified workers before emigrating. Their work experience is characterized by isolation, subordination, high intensity of work and emotional stress. Many live-in caregivers are in close contact 24 hours a day with the person they care for. The inevitable consequence of this circumstance is a negotiation of privacy, which on both sides is a very thin line. Caregivers are there at the elderly person’s most vulnerable moments: they change them, wash them, feed them. They experience their employers’ homes as if they have always been part of them, sleeping in their children’s old rooms and moving from place to place as old family photos hang on the walls watching their movements. However, they are also forced to compromise their personal space, finding themselves in an environment they call “home” but that is not entirely accurate. When they are allowed to take a break from work, they continue to sense the presence of the person they care for, and are on the alert if the person calls out, in need. Bedrooms become the live-in caregivers’ shelters. Days are punctuated by the phone ringing and the latest updates coming to check attacked areas, for fear that their friends or family might be affected. Familiar terms arise when referring war or conflict, such as invasion, borders, loss, compromise, withdrawal and irruption. In their own way, caregivers also experience these terms in their daily lives in an unfamiliar country: invasion of physical and emotional personal space, negotiation between the two sides, loss of their intimacy and withdrawal from their homeland and family. They are living through a war from afar and facing a conflict within themselves.

This story was supported by The Alex and Rita Hillman Foundation Fellowship.

Link for the multimedia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aknC4lbP3fM&t=2s